[javascript protected email address]

James Condliff, Liverpool

Circa 1833

Sold

Height without base & dome: 12 inches

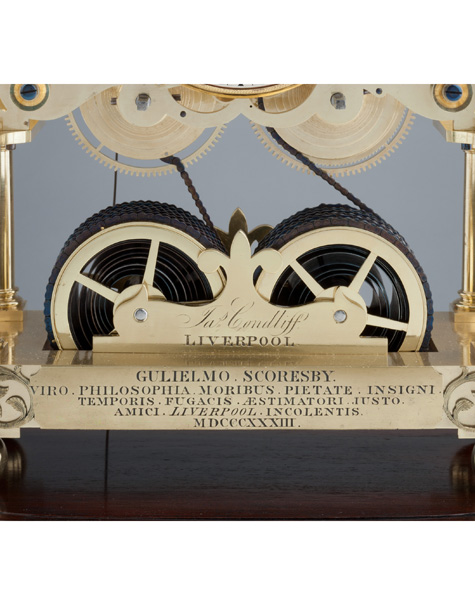

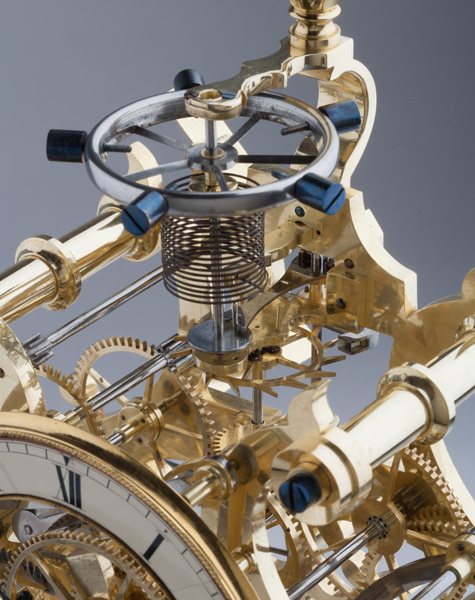

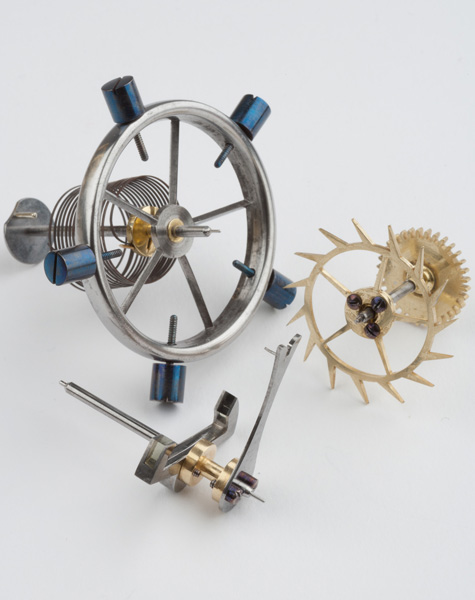

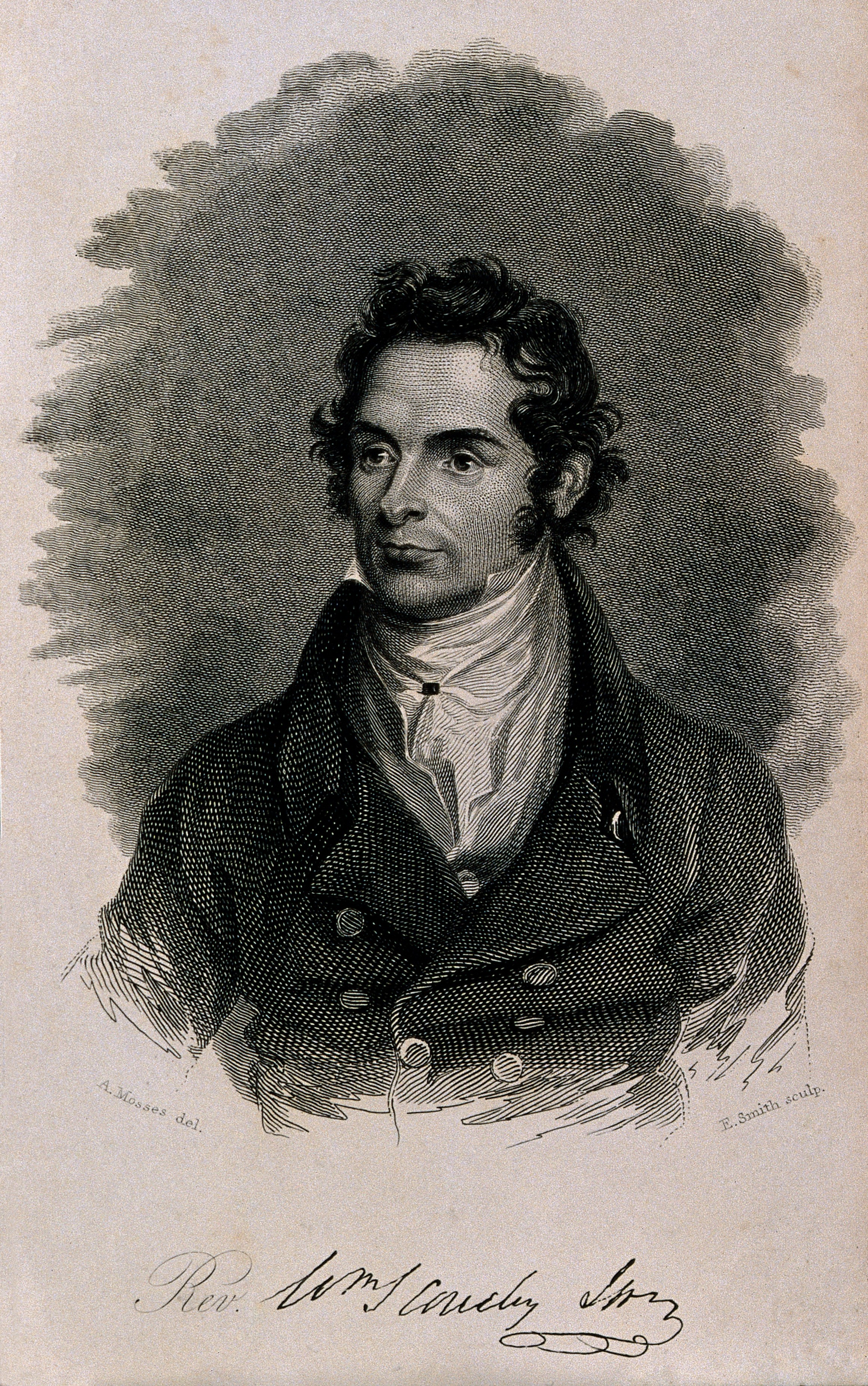

A very fine and historically important balance wheel striking skeleton clock. Type: Series One/Two DIAL The centrally positioned dial has an annular white enamel chapter ring with Roman chapters and outer minute divisions. The blued steel hour and minute hands are of Breguet form, the longer delicate counterbalanced seconds hand has an arrowhead and the dial is framed by a concave-moulded brass bezel with milled decoration. FRAME The pill-and-scroll frame is of transitional form – i.e. betwixt the first and second series. The rectangular brass base is raised on ball feet which; the front of the base is applied with a brass dedication plaque with nicely pierced and engraved floral terminals; the plaque is engraved with the following dedication GULIELMO SCORESBY VIRO . PHILOSOPHIA . MORIBUS . PIETATE . INSIGNI. TEMPORIS . FUGACIS . AESTIMATORI . JUSTO . AMICI . LIVERPOOL . INCOLENTIS. MDCCCXXXIII To William Scoresby A man distinguished for his love of learning, character, piety, a valuer of fleeting time and an upright staunch friend. An inhabitant of Liverpool 1833 The pillars, separating the base from the, scroll movement frame, are finely cast with finely modeled capitals and bases; they are all surmounted by a tulip-shaped finial each of which is punch-dotted for their individual corner positions. The wheel train is held within two identical scroll-pierced frames held together by four baluster pillars which are secured to the front plate with blued steel screws and pinned to the backplate. The whole machine is surmounted by a further brass tulip finial. WHEEL TRAINS The two springs are clearly visible through their five-spoked caps either end of the brass barrels; the barrels themselves are recessed into the rectangular base and pivot at the back on a fleur de lys shaped brass bracket with ratchets out of view, and at the front on a similar shaped bracket signed by the maker Jas. Condliff LIVERPOOL. The blued steel chains slant upwards and wind onto two fusees each with six spoked great wheels; the end cap on the strike train removed to display the ratchet-and click, the going train having full cap for the maintaining power with delicate curved clicks. The going train has delicate wheels each with five spokes, the contrate being screwed to the collet and driven from a solid intermediary wheel (or pinion). The escapement is unique to Condliff’s skeleton clocks and has a very large diameter horizontal steel balance wheel with five V-shaped spokes and five outer timing screws; the balance with pivoted at the top and base within a jewelled end stone; beneath the balance is a large blued steel helical spring above the escapement which is jewelled pallets and a five-spoked escape wheel. The strike train operates via a rack-and-snail, which is clearly visible in the dial centre; all the delicate wheels in the strike train have five spokes and are attached to their collets with three blued steel screws. The hours are struck on a steel gong in the base via a steel lifting arm at the rear of the movement. WILLIAM SCORESBY (photographed above) The Early years Scoresby was born in the village of Cropton near Pickering 26 miles south of Whitby in Yorkshire. His father, William Scoresby Senior (1760–1829), made a fortune in the Arctic whale fishery and was also the inventor of the barrel crow's nest. The son made his first voyage with his father at the age of eleven, but then returned to school, where he remained until 1803. After this he became his father's constant companion, and accompanied him as chief officer of the whaler Resolution when on 25 May 1806, he succeeded in reaching 81°30' N. lat. (19° E. long), for twenty-one years the highest northern latitude attained in the eastern hemisphere. During the following winter, Scoresby attended the natural philosophy and chemistry classes at Edinburgh University, and again in 1809. Career In his voyage of 1807, Scoresby began the study of the meteorology and natural history of the polar regions. Earlier results included his original observations on snow and crystals; and in 1809 Robert Jameson brought certain Arctic papers of his before the Wernerian Society of Edinburgh, which at once elected him to its membership. In 1811, Scoresby's father resigned to him the command of the Resolution. In the same year he married the daughter of a Whitby shipbroker. In his voyage of 1813, he established for the first time the fact that the polar ocean has a warmer temperature at considerable depths than it has on the surface, and each subsequent voyage in search of whales found him no less eager of fresh additions to scientific knowledge. His letters of this period to Sir Joseph Banks, whose acquaintance he had made a few years earlier, no doubt gave the first impulse to the search for the North-West Passage which followed. On 29 June 1816, commanding the Esk on his fifteenth whaling voyage from Whitby, Scoresby encountered grave problems when ice damaged his ship. With the aid of his brother-in-law's crew on board the John, and after agreeing to surrendering much of their catch, the Esk was repaired, of which Scoresby recounted in his 1820 book The Northern Whale-Fishery.[1] In 1819, Scoresby gained election as a fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and about the same time communicated a paper to the Royal Society of London: "On the Anomaly in the Variation of the Magnetic Needle". In 1820, he published An Account of the Arctic Regions and Northern Whale Fishery, in which he gathers up the results of his own observations, as well as those of previous navigators. In his voyage of 1822 to Greenland, Scoresby surveyed and charted with remarkable accuracy 400 miles of the east coast, between 69° 30' and 72° 30', thus contributing to the first real and important geographic knowledge of East Greenland. This, however, proved the last of his Arctic voyages. On his return, he learnt of his wife's death, and this event, with other influences acting upon his naturally pious spirit, decided him to enter the church. He then began divinity studies at Queens' College, Cambridge[2] and became the curate of Bessingby, Yorkshire.[3] Meantime, his Journal of a Voyage to the Northern Whale Fishery, including Researches and Discoveries on the Eastern Coast of Greenland (1823), had appeared at Edinburgh. The discharge of his clerical duties at Bessingby, and later at Liverpool, Exeter and Bradford, did not prevent him from continuing his interest in science. In 1824, the Royal Society elected him a fellow, and in 1827, he became an honorary corresponding member of the Paris Academy of Sciences, while in 1839, he took the Doctor of Divinity degree. From the first, Scoresby worked as an active member and official of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, and he contributed especially to the knowledge of terrestrial magnetism. Of his sixty papers in the Royal Society list, many relate to this department of research. However, his observations extended into many other departments, including researches on optics and, with James Joule, comparing electromagnetic (chemical), thermal (coal/steam), and organic (horse) power sources.[4] The Rev. Dr. William Scoresby by Edwin Cockburn To obtain additional data for his theories on magnetism, he made a voyage to Australia in 1856 on board the ill-fated iron-hulled Royal Charter, the results of which appeared in a posthumous publication: Journal of a Voyage to Australia for Magnetical Research, edited by Archibald Smith (1859). He made two visits to America, in 1844 and 1848; on his return home from the latter visit he made some valuable observations on the height of Atlantic waves, the results of which were given to the British Association. He interested himself much in social questions, especially the improvement of the condition of factory operatives. He also published numerous works and papers of a religious character. In 1850, Scoresby published a work urging the prosecution of the search for the Franklin expedition and giving the results of his own experience in Arctic navigation. Scoresby married three times. After his third marriage (1849), he built a villa at Torquay, where he was appointed honorary lecturer at the Parish church of St Mary Magdalene, Upton. He died at Torquay on 21 March 1857. He is commemorated by a memorial in Upton church, which is decorated with mariner's compass and dividers, and a bible. A number of places have been named after William Scoresby, including: The Lunar crater Scoresby Scoresbysund, now Ittoqqortoormiit on the east coast of Greenland The Scoresby Sund fjord system[6] The Melbourne suburb of Scoresby, Victoria in Australia, which is 25 km southeast of the CBD RRS William Scoresby, an early-twentieth-century research vessel in the employ of the British scientific organisation, Discovery Investigations Scoresby Land in Greenland Cape Scoresby (66°34′S 162°45′E / 66.567°S 162.75°E / -66.567; 162.75), bluff marking the north end of Borradaile Island. References in literature Herman Melville's main character Ishmael quotes Scoresby in the Cetology chapter of Moby-Dick: "'No branch of Zoology is so much involved as that which is entitled Cetology,' says Captain Scoresby, A.D. 1820."[7] Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy features a character named Lee Scoresby, an intrepid explorer, old Arctic hand, and balloon aeronaut. Pullman has stated that the character was named after William Scoresby and Lee Van Cleef.[8] William Scoresby also had a habit of making polar bears pets for friends.[9] H. P. Lovecraft refers to William Scoresby's illustrations when describing an Antarctic mirage in the story 'At The Mountains of Madness'[10] Julian Barnes references William Scoresby in his postmodern novel "Flaubert's Parrot" that reads like a literary criticism. In the fourth chapter where the author is discussing what kind of bear Flaubert thought himself to be, he states that William Scoresby claimed the liver of the polar bear to be poisonous. The list of contributors to finance the purchase of the skeleton clock, taken from William Scoresby’s personal papers at the Whitby Museum.