[javascript protected email address]

Jeremy Evans

Tompion Expert and ex museum curator

What was your childhood ambition?

I don’t remember having one but I was always fascinated by museums and their contents because my father was the curator of local museums at Hitchin and Stevenage. The day before I was born he required hospital treatment after a 17th.c. lantern clock fell from the top of a cupboard and landed on his head. Something of an omen perhaps?! An avid collector by the age of nine, my room was full of bits of broken clay pipe, old bottles, potsherds, skulls (not human), feathers, buttons, tea-cards, horseshoes, bubble-gum wrappers, matchboxes, bus tickets, train tickets, glass, cheese labels, stamps, fossils, coins, shrapnel, shells, signs, stones, keys, stuffed animals and birds, marbles (glass), tins, flags, etc, etc., but no watches or clocks. I began to get interested in clocks after buying a couple in local junk shops when I was in my early teens, and at about the same time my mother started collecting 19th.c. American shelf clocks. These often needed repair and they provided a valuable, if very basic, introduction to horological mechanisms.

Who are your heroes?

There have been several. My great great great grandfather Daniel O’Connell tops the list - particularly because of his influential contribution to anti-slavery legislation in the early 19th century. My earliest hero was Horatio Nelson - as a seven year old I had a picture of Him above my bed and I remember getting a gold star at junior school for knowing the date of the Battle of Trafalgar. More recently, Robert Hooke on account of his extraordinary and invaluable journal and, of course, Thomas Tompion.

Who has been the greatest influence in your life?

My parents.

What is your favourite clock?

It is not possible to pick just one, but favourites would include, by Tompion, the box-wood night clock, the year-going Mostyn, the two metal-cased dual-control balance/pendulum clocks, and the Greenwich year clocks. To these might be added the Dover Castle clock at the Science Museum, and three more clocks in the British Museum’s collection – the monumental Habrecht, the Vallin musical clock, and the Fromanteel long-duration timepiece.

What is the most satisfying clock you have ever had the privilege to work on?

All of those favourites listed above.

What annoys you most about horology?

Over-zealous restoration and erroneous, irreversible restoration which has been based on insufficient evidence.

As far as my interest in Tompion is concerned the most regrettable aspects are my inability to locate any contemporary reference relating to the production or supply of the Mostyn Tompion, the inability to locate any firm evidence of his formative “apprenticeship” years, and the inability to locate the inventory of his estate drawn up after his death – but see also the dream dinner-date below!

What building do you admire most?

Again, it is not possible to pick just one, but those I most admire include Stonehenge, St Paul’s Cathedral, the British Museum and Reading Room, Chatsworth – and for their beauty in idyllic settings, Rievaulx Abbey and Powys Castle.

Who is your favourite architect or artist?

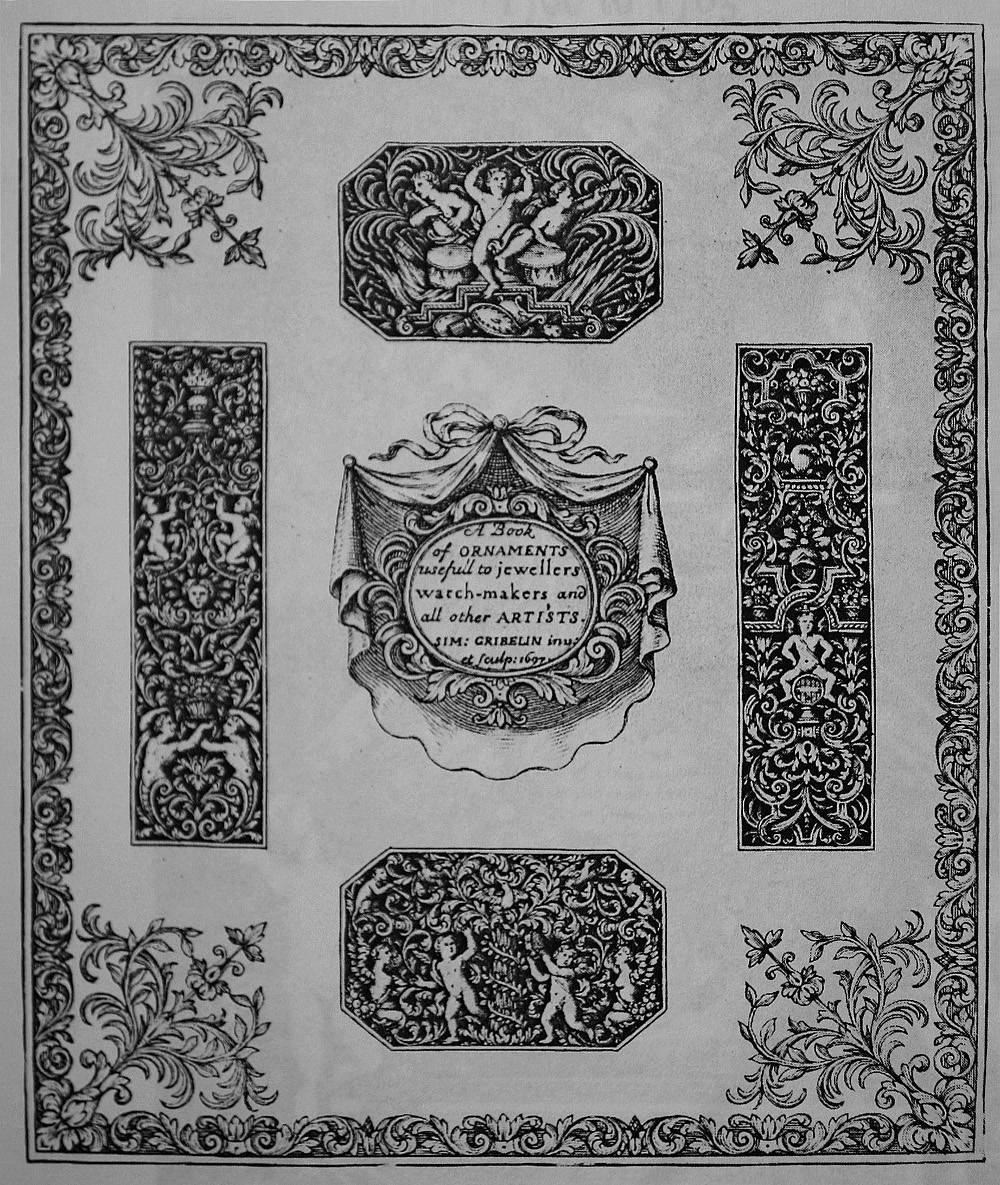

The designer/engraver Simon Gribelin.

What do you like to do in your spare time?

As far as horology is concerned I enjoy working on – adding to and enhancing - the various lists I have been compiling over the years. These include the already published Tompion and Graham clock, watch and instrument lists, as well as those of the work of Tompion’s employees and associates, particularly the Delanders. Lists of engravers, gilders and clock-case makers have also been compiled, along with lists of Quare watches and clocks – it is hoped that some of these will be published soon. With fresh material being continually added to the web the range of on-line research is vast and exciting details are still turning up. It is impossible, however, to keep up with it all. Otherwise, my chief employment centres around the happiness and welfare of Sparky - an extremely needy Yorkshire Terrier. This requires an awful lot of sitting, so I have to enjoy far too much television - history, geography, science, astronomy, nature documentaries, general knowledge quiz shows, Antiques Roadshow, and sport – rugby, football, cricket, snooker, motor racing and cycling. I am retired – I can do what I like! Pool (no, not swimming) and cards – four-card brag, every Friday night! And a bit of warm-weather gardening. Can’t cook and don’t travel – have been further than a hundred miles from home only once in the last ten years.

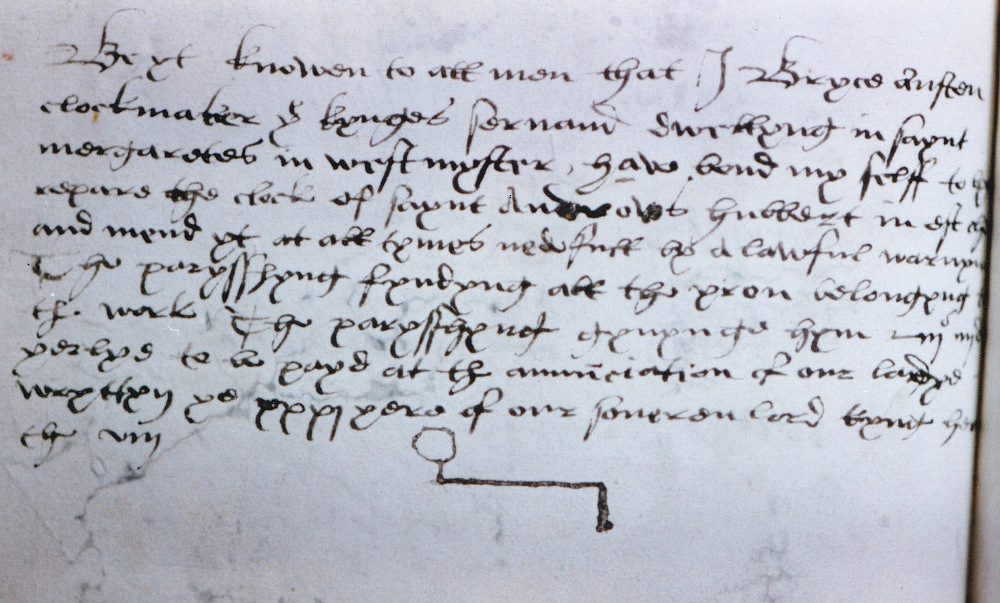

What would be your dream luxury, money no object?

A full set of microfilms of London’s 16th -18th century parish and livery company records and of all royal accounts of the same period, together with the time to read them. In the early 1980s I began a survey of London’s pre-1720 church clocks based on the numerous entries in parish churchwardens’ and vestry accounts. These records were amongst the most enthralling I ever had the pleasure to peruse, and searching them had all the excitement of a treasure hunt! This work was abandoned in favour of Tompion and was never completed.

If you could change one thing in the world, what would it be?

The direction of rotation – it would be very interesting to see what would happen. And maybe my car.

If you were to write another book, nothing to do with horology, what would it be about?

I would not wish to write about any other subject.

If you could meet, and have dinner with one person, past or present, who would it be and what would you ask?

Only one answer to this question – Thomas Tompion – and I would ask him to tell me his life story. It would be a very long dinner. Of particular interest would be his formative years – why did he leave Northill, who was responsible for his early training, who inspired him, and where was he between 1650-1671. Did he witness the Great Fire? Had he received encouragement, instruction or support from Edward East, the Fromanteels, or Samuel Knibb, or from somebody else?

To get him in a good mood I would tell him that he was still highly revered in the 21st century, and that 99% of the clocks he made that had survived were still working accurately after over 300 years. I would ask him to tell me about his skills, to describe in detail the workshops and their tools, and to clear up the uncertainties regarding the introduction and evolution of the various numbered series of items. Had he made any types of item of which we are unaware? I would ask about his working relationship with Hooke and his dealings with Sir Jonas Moore. I would also show him the list of employees and apprentices of whom we are aware and ask him to explain who did what and where, and to fill in any missing details. How many clock case makers did he employ, and how many turret clocks did his business produce? And, of course, I would want to take a look at the watch he carried and find out why he thought it special – was it a timepiece, repeating watch or clockwatch?

One thing he would not be able to help with would be what happened to the shop and workshop ledgers, but I would have asked him to bring them along to the dinner so that he could give me a guided tour of them. He would, of course, be encouraged to embellish this perusal with anecdotes relating to the various customers and their purchases, especially those items made for royalty. I would ask about designs – were preliminary sketches made on the backs of snuff wrappers? Was he a skilled draughtsman capable of drawing up precise designs of the mechanisms he produced? Were these kept in a ledger?

I would ask his opinion of the relatives who were near him in London, in particular his wayward nephew Thomas, and his neice Elizabeth who married George Graham. And what did happen to bring about Edward Banger’s departure and the demise of the Tompion – Banger partnership? In order to know Thomas’s character more intimately I would also have to ask him about his sexual orientation, whether he had lovers – was there a “love-of-his-life”, and whether he ever contemplated marriage? Had he ever been hurt by any failed romance?

In short, I would be interested to hear about any aspect of his life – his health - did he smoke or take snuff (his nephew-in-law Thomas Nodes was a tobacconist almost opposite his shop in Fleet Street), did he wear glasses, was he very religious, where did he learn to read and write, did he like, and own, dogs, what were his favourite foods and drinks, did he ever get drunk, was he ever despondent, and if so, about what, what was his favourite reading material – did he have a library, did he enjoy music, did he learn any other languages, what were his prized possessions, did he collect any artefacts – horological, scientific or otherwise, did he have a collection of astronomical instruments – he probably carried out observations from his roof, was he frightened of heights, did he hunt, shoot or fish, did he ever break any bones, did he suffer from toothache, was he ever robbed or challenged by highwaymen or footpads, had he ever been burgled of stock, did he ever fight, did he ever commit a crime, what made him laugh, what made him cry, what frightened him, what was the most embarrassing moment of his life, what was his greatest regret – if he had any, was he a good horse rider, did he write letters (if he did, none are known to have survived), what did he dream about at night, did he ever witness public hangings, did he ever gamble, did he wear a ring with his seal, etc, etc? On slightly dodgy ground I would ask him he would mind very much if his remains were exhumed in the 21st century for scientific analysis?

And lastly, I would ask him if he would be happy to complete an interview questionnaire for my dear friend Mr. Benjamin Wright – only a few questions – tackle them over the coffee.