[javascript protected email address]

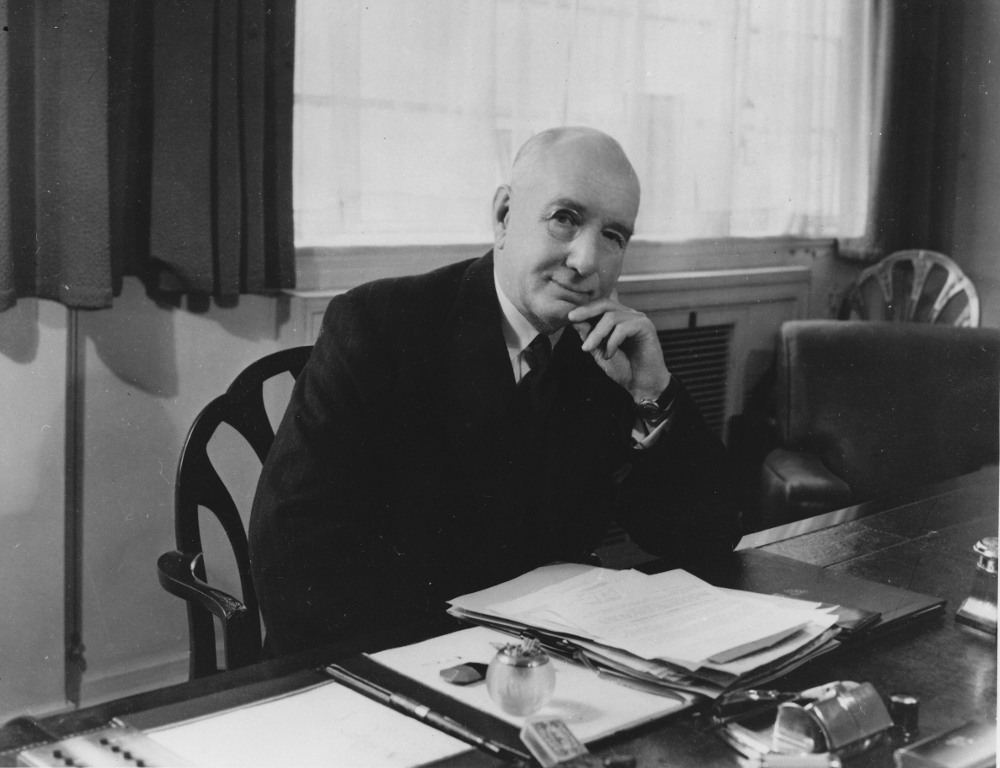

Dr James Nye

Chairman of the Antiquarian Horological Society

I imagine it must be both daunting and very exciting to be the new Chairman of the AHS, what changes and improvements to our beloved society would you most like to see made under your tenure?

I see no merit in change for change’s sake, and there is much the Society does well that I will look to nourish and protect. Horological societies, like every other society round the world, face challenges in maintaining their membership numbers. Under David Thompson’s chairmanship we have worked very hard to reverse declines in numbers and those efforts have now paid off, with the beginnings of growth emerging once more. I will continue the drive towards making the society a welcoming, friendly and inclusive place that offers something of interest to a broad church of collectors and enthusiasts interested in the material culture and history of timekeeping.

An exciting development that I have been involved in encouraging is the emergence of a Wristwatch Group – a development long in the making and rather overdue, but one which I am sure will be of great satisfaction to a large number of existing members, and which will crucially bring new members into the fold. We’ve all seen people at AHS meetings for years, pulling wristwatches out of their pockets to compare notes with their friends – now there will be more of a forum for those members.

Above all I want to make sure the Society continues to be a place that offers huge fun to its members through its meetings and activities, where the standards of its publications and lectures are maintained at the highest level.

What was your childhood ambition?

From an early age I collected Dinky and Matchbox toy cars, and my pride and joy were various Rolls Royce models. At about the age of ten, my mother took me to London and we went to Berkeley Square, and into Jack Barclay.

A salesman let me sit in the driving seat of a Corniche coupé, and I am sure it was the first time I ever smelt the intoxicating scent of Vaumol leather, and I remember too the explanation of the mirror-veneered dash.

The childhood ambition I recall is wanting to own one of these cars some day. I don’t expect I shall ever drive a new one away from Jack Barclay, but a while back I did have some fun for a few years, owning a Silver Cloud 3, nearly the same age as me.

Who has been the greatest influence in your life?

The Reader’s Digest used to have a feature called ‘My Most Unforgettable Character’ and I know my father enjoyed it. He wrote an essay for my sister and me based on it, and sketched not one, but the ten most important people in his life. In the same vein, I have tried a similar exercise, and it comes down to singling out the people that were the most influential, who gave you a key job, or mentored you, or opened your eyes to something important.

There are various teachers and business partners that have been huge influences on my life, allowing me any success I have enjoyed, but in this context the most influential man would have to be the late Assistant Chaplain at Ardingly College, the Rev. Nick Waters. In a mad and chaotic household he maintained a packed workshop with two benches, Schaublin lathes, cleaning machines, the works.

He repaired watches as a sideline, but, crucially, he offered a very small number of us – those not very good on the rugby pitch – the chance to spend afternoons cleaning and repairing English dial movements and French drum clocks. From the age of thirteen, I spent countless teenage hours at the bench, also taking up responsibility for the school’s Gents-based clock system, complete with ‘waiting-train’ turret clock, bell programmer, and so forth.

My teenage immersion in practical horology, and particularly in electrical horology, has informed the rest of my life, for a lot of time as background colour, but more recently as the main feature.

So Nick Waters has to be the greatest influence, really.

Who is your hero?

Well, my eldest daughter is called Hero, so I can offer her as a candidate!

Or perhaps it should be her mother, Luci, who can’t be anything other than heroic to put up with the ceaseless round of clock-related matters, from dawn till dusk, not five but seven days a week…!

What is your favourite clock?

The curator’s nightmare question! John Taylor’s answer was a good one – to describe them all as children – how can one be a favourite? I could also say ‘the one I think I am about to buy’, whatever that is at any one time – and by the way I am definitely trying to stop acquiring any more!

Another answer, perhaps closer to the mark, would be to say that my allegiances shift, and usually lie with the clock that is at the heart of my most recent research and writing.

In other words the physical object that magically or romantically puts me in touch with characters involved in its creation.

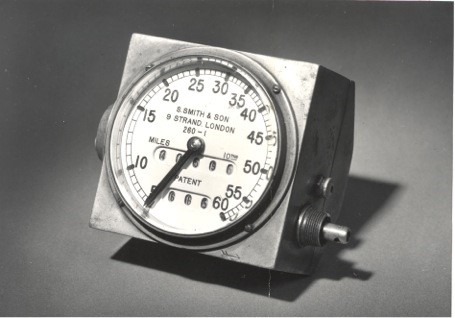

Writing A Long Time in Making I surrounded myself with speedometers, fuzes, alarm clocks, watches and mine-timers made by Smiths, because they spoke to me about the firm I was researching, and the humblest objects offered soothing words of encouragement during late night drafting.

Who is your favourite architect and which building do you most admire?

Growing up in a somewhat Gothic Victorian school and then spending time in a largely Neo-Gothic college at university, I am sentimental about that feel, and therefore might have selected the Midland Hotel at St Pancras as the building I most admire.

However, I think my favourite buildings are the handful of magnificent modernist houses built in the UK after the Great War. I admire FRS Yorke’s designs, and have his book The Modern House. His friend Amyas Connell designed High and Over House at Amersham, much in the news recently, but favourite of all would be High Cross House in Devon, designed by William Lescaze.

What would be your dream luxury, money no object?

This comes back to childhood ambitions. I think it would have to be Rolls Royce Phantom Coupé. But mindful of Ettore Bugatti’s comment, I am putting this off until I have a ‘heated motor house’.

Who is your favourite artist and which painting do you most admire?

I am drawn to Nevinson and his Great War paintings, but to live with one must be challenging. About the only time I wonder what it would be like to own a major painting is when I’m walking round the Peggy Guggenheim collection in Venice, where even though it’s a monster house, there is a less of the feel of being in a museum.

I might be strongly tempted by Picasso’s Le Poète or Braque’s The Clarinet, but ultimately the one artist whose works I most covet is René Magritte, and the version of Empire of Light in the Guggenheim would do nicely.

If you could change one thing in the world, what would it be?

Where does one start? Leaving aside all the obvious ills one might cure, there is a more insidious characteristic of our modern society which I would dearly love to change. It is the tendency to short-termism, in virtually every walk of life, but chiefly in matters of both investment and public policy.

The regulatory and fiscal framework has altered vastly over the last thirty years, to the disadvantage of equity as an investment method. Our pension funds and the whole world of investment management have tended to move away from equities to a mix with a significantly greater proportion of debt securities than was traditionally the case.

Mark-to-market standards and the modern reporting cycle force short-termism on CEOs and their finance directors, whose decisions are driven on what the current quarter’s figures will do to a share price – and less driven by the long-term outcome. It is very hard to imagine any ten or twenty-year planning, in any arena. If new energy plants take perhaps twenty years from inception to being on-stream – four times the life of a UK government – it is no wonder politicians fail to achieve consistent and coherent thinking.

We need to find ways once more of making it attractive to think long-term, to plan long-term and to invest long-term.

If you could meet and have dinner with one person, past or present, who would it be and what would you ask?

I’d pick Sir Allan Gordon-Smith. I spent nearly two years looking at the history of Smiths, and he is without doubt the central figure in the story. Born in 1881, he masterminded the transformation of the business from a small family concern into a serious international engineering company, organised as an efficient managerial enterprise.

He died in 1951, and while I feel I did his life justice in my account, there are hundreds of questions I could ask that would help illuminate further his remarkable story – whether cheekily checking the true story behind the speedometer in Edward VII’s Mercedes, to verifying hair-raising stories of hedge-hopping in France in the Second World to arrange vital supplies to be smuggled, or to learn what it was like in the Ministry of Aircraft Production.

He was an intensely clubbable man and would no doubt drink me under the table, but it would make for a lively evening.

If you were to write another book - nothing to do with horology, what would it be about?

That’s an easy one, as it is largely written! I am fascinated by the raising of equity capital in the late Victorian and Edwardian periods, especially in relation to new technology companies. How was the money raised, by whom, how did the system work, and why are the reputations of those involved so terrible?

I have spent years studying the company promoter, his methods, his successes and a lot of the failures. With a following wind, the finished book might emerge in 2016–17.

What is your biggest horological bête noir

A ‘bête noire’ implies something more serious than a punched pivot-hole or other such bodge. Something that has me hot under the collar at present is the emerging vogue for a few modern watch companies, often non-British domiciled, to centre their pitch around a bogus claim to long-standing British heritage – perhaps reviving as a brand the name of a long dead but much revered British pioneer.

I imagine the letter of the law may be scrupulously observed, but what a nasty taste in the mouth the whole practice leaves – I think that might qualify as my personal bête noire’.

It's perhaps a little morose, but how would you like to be remembered?

I have put a lot of effort into horology in one way or another over quite a long time, for example running the AHS Electrical Horology Group for near eighteen years. It gives me a huge kick to arrange lectures, visits, tours, excursions, whatever, that people really enjoy and remember – and I certainly enjoy presenting my own research.

In recent years, establishing The Clockworks Museum as a centre for people to visit, conduct research, attend meetings, solve conservation and repair problems etc etc, has been a vastly satisfying project, and one which I hope will continue to go from strength to strength. We have hundreds of visitors, both expert and many more newcomers to the field, and the exchanges will all of them are heart-warming and satisfying.

I have had the opportunity to contribute to people’ enjoyment of the subject both through the AHS and the Clockmakers Company and hope to do so for many years to come. If it ends up being remembered, that will be a great reward.