[javascript protected email address]

Matthew Read

Head tutor at West Dean College

You have been a professional clockmaker, a museum curator and now a teacher - which do you enjoy most?

In relative terms, the latter. As a professional clockmaker there is - at least in theory - a degree of freedom. The reality however is often one of very long days and making ends meet, interjected with occasional moments of satisfaction and fulfilment. As a curatorial assistant and conservator, I had the great privilege of working with some of the World's finest horological artefacts and alongside highly respected professionals. This was a privileged beginning in the word of professional horology. As a teacher however, I have the opportunity to disseminate skills and knowledge gathered during my 25 years in horology, and in a way I feel I am a contributor to the common horological good. Hopefully my students will play their part in the future of horology, therefore the latest phase in my career has to be the most satisfying and worthwhile.

Describe one of your routine days

Mid-life has ruined my sleep pattern, so on occasion it is easier and productive to start work early when the house is quiet. Following the chaos that is children preparing for their day and the school run- it's a pleasurable ten minute amble through the village to 'the office'. Our programme at West Dean is primarily bench-craft based, so the majority of my 9-5 time, four days per week is spent teaching clockmaking. One of the advantages of living on the estate here at West Dean is a one minute commute. Therefore following dinner with the family, it may be back to the office for an hour or so - before retiring with a copy of AH of course!

What is your favourite clock?

Dent 1906, the sidereal standard of 1870. This clock is arguably the ultimate development (Harrison aside some might say) of the seconds pendulum in 'free air'. It is a physical representation of horological theory as refined by George Biddell Airy. It incorporates Airy's interpretation of the spring detent escapement for pendulum clocks, a massive bronze casting for the pendulum support, zinc and steel compensation with auxiliary compensation, and barometric compensation. The clock is superbly made throughout and set new standards for timekeeping. The tank regulators that followed were, in their own right, superior, but somehow, in my view, progress from what is effectively a direct and logical development of eighteenth century horology towards modern time-keeping instrumentation. Dent 1906 marks the end of an era.

What aspect of your job gives you most satisfaction?

Witnessing the progress of students, particularly in developing bench craft skills such as filing flat; a great art and joy to witness when done well. The proper development of these skills takes thousands of hours and is, quite simply, hard work. Those students who posses the necessary tenacity make significant improvements not only to their hand skills, but wider understanding of horology, which brings a great deal of reward. Equally satisfying is when a student flies the college nest and makes their first steps in the world of professional horology.

What aspect of your job would you most like to change/develop?

New Making. The conservation of historic objects is already well defined and widely practiced at a professional level. Sustained energy and focus will, I feel, inevitably ally horology closer to the wider international view. With new making however, within the past couple of decades, both abroad and more recently at home, there has been an explosion of creativity and interest in the design and making of wristwatches, many incorporating new manufacturing technology and modern materials. I see no reason whatsoever that this wave of excitement and innovation cannot in some way be translated to clocks. Investment is of course needed, and West Dean could be well placed to play a significant part in a wider new making initiative within clockmaking.

Which is your favourite museum?

Predictably I feel a certain sense of belonging at the Royal Observatory at Greenwich. Entering the wrought iron gates on Blackheath Avenue never fails to raise the heart rate. Most of the collections there are related directly to the site, making for a rich contextual interpretation. It is a museum where with a little imagination, one can quite easily picture a significant moment from the past.

If you were able to share dinner with anyone in the world, past or present, who would it be?

My wife Marina, and my two children aside, within horology today there are a charming, informed and entertaining people who I know reasonably well who always make good company. I have no nostalgic ambition, although dinner with Thomas Earnshaw in full flight might have been interesting.

What is your favourite building?

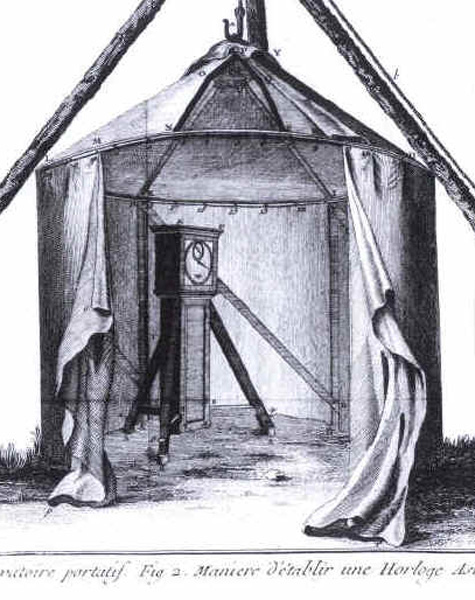

Horologically, I have interest in those temporary buildings used to house instruments used in the nineteenth century transits of Venus. The idea of long sea voyages to distant corners of the World sounds rather romantic. Rather like camping however, the reality was not as rosy. Outside the horological world, the now Little Chef restaurant by Sam Scorer at Markhan Moor on the Great North Road with its hyperbolic paraboloid roof punctuates childhood memories; the edge of the then known universe. For me this building represents the challenge of preserving our 20th century heritage. Incidentally, the hyperbolic paraboloid design has been used for the roof of the new 2012 Olympic velodrome. The double helix ferro-concrete subterranean car park under Bloomsbury square is another high on this list, as were the (now replaced) R.A.F. Fylingdales long-range tracking station 'golf balls', high on the Yorkshire Moors.

If you could own any car, what would it be?

A new four-seater Morgan in burnt orange would be a fine luxury, but as the saying goes, not in this lifetime. The very thought of being stranded at the side of the road with the contents of the crankcase strewn across the tarmac discounts vintage motoring. I did however recently come across an owner's manual for a Bentley S3. The preface reads 'The Bentley S3 is designed and built to very high standards of precision and quality and before leaving the factory, the car is thoroughly tested and adjusted by experts'. Is that alone good enough reason to buy the car? In addition, the car has cigar (not cigarette) lighters and picnic trays. As horologists appear to have a weakness for this marque, this is my little toe in that rarefied world.

What is your most satisfying restoration?

I have been in the privileged and fortunate position of working on some very fine and valuable objects, and there is of course always an element of satisfaction in restoring the dynamic nature of horology. The most satisfying restorations for me today, are sometimes those clocks that may otherwise be discarded or overlooked. A rescue; a modest American clock I bought recently at a local auction for one pound, that has written across the dial in felt-tip pen 'scrap'. The clock has been modernised with a mid-20th century Fablon type finish, and is a great case study in the wider view of preservation, and advocate for the on-going debate that accompanies the often-difficult decision-making process associated with such restorations. It is not just the great names that deserve our attention, lesser clocks are sometimes neglected due in part to their lack of monetary value.

Can clockmaking be taught, or is it a gift?

If those virtues of will, tenacity and investment are available, I feel it can be taught to most. Naturally, for some it is easier than others. In the maintenance and repair of clocks, fault finding and subsequent effective remedial attention are the key to success, but this area of skill can be difficult to teach.

Who has been the biggest influence in your (horological) life?

In my earlier days, tutors at the Institute including Alan Timmins and John Read inspired and encouraged me. Those enthusiastic views were equally opposed by those with a less than rosy outlook on the future of horology. It was ultimately those who saw a bleaker picture who drove me to prove them wrong; a pig-headed Yorkshire trait maybe, that lead me to a formative period at the bench of Roger Still at West Dean College. However my time at Greenwich was undeniably, and continues to be, my most influential and inspirational influence.

Clockmaking at West Dean - does it have a future?

Absolutely, and without doubt. At least as the professional horologist is concerned, there appears to be a very bright future ahead. In most fields, the most skilled and capable have the opportunity for continuous and fulfilling occupation. In our field, we are in the fortunate position where demand for work outstrips the supply of competent practitioners. From my personal perspective, those with a robust and positive attitude to the preservation of historic work are in the strongest position. There will always be a continual demand for top-level clock restorers.